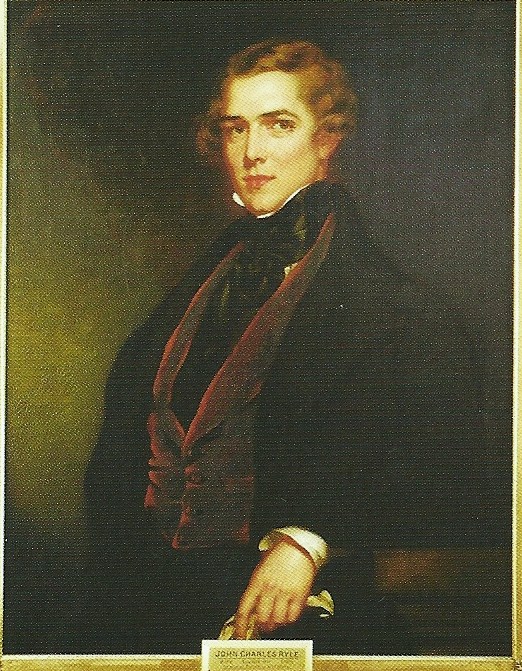

The Life of John Charles Ryle (1816 - 1900)

John Charles Ryle was born on 10 May 1816 at Park House, Macclesfield, the eldest son of John Ryle, who was a private banker and a local MP. His mother was Susanna, the daughter of Charles Hunt of Wirksworth, Derbyshire. The Ryle family began as Methodists, going back to the days of the Wesleys, but this was replaced by an ‘unenthusiastic conformity’ to the Church of England.

Ryle was educated at Over, Cheshire from 1824-7, after which he was sent to Eton in 1828. In 1834 Ryle proceeded to Christ Church, Oxford as a Fell Exhibitioner in 1835. He became the Craven Scholar in 1836 and graduated in 1838; he subsequently gained his MA in 1871 and was created a DD, by diploma in 1880. At university he was a fine athlete who rowed and played Cricket (as captain of the University eleven). He ended his student life by taking a first class degree in Modern Greats and was offered a college fellowship (teaching position) which he declined.

Ryle had experienced conversion in 1837 through the counselling of his friend Algernon Cooke and in 1838 the powerful impression on him of a text in Chapel at Eton.[1] Reflecting on his conversion, Ryle said, “Nothing to this day appeared to me so clear and distinct as my own sinfulness, Christ’s preciousness, the value of the Bible, the absolute necessity of coming out of the world, the need of being born again, and the enormous folly of the whole doctrine of baptismal regeneration.”

Ryle had been raise a Methodist and he had a great-grandmother who had been converted by John Wesley, but Ryle was ordained into the Church of England on 12 December 1841 by Bishop Charles Sumner at Winchester, although he had originally intended to pursue a career in politics. Ryle had grown up in a wealthy home, wanting for nothing, heir to the family fortune, in pursuit of a banking career, walking in his father’s footsteps. In June 1841, however, his father’s investments collapsed and instantly his whole future changed. “We got up one summer’s morning with all the world before us as usual, and went to bed that night completely and entirely ruined.” He described that experience as “the blackest chapter of my life.” By fall of that year he applied himself to Christian service. “I became a clergyman because I felt shut up to do it and saw no other course of life open to me.”[2]

He took a curacy at Exbury in Hampshire (1841-3). “He was required to provide not only pastoral care, but also medical advice to his flock.”[3] Although he was less than complimentary about his congregation of mostly agricultural workers, his preaching soon filled the church.

He became rector of St Thomas's, Winchester (1843-4), and summed up the spiritual state of Winchester as “The whole place is in a very dead state ... worldliness reigned supreme in the close.”[4] Ryle rose to the challenge and soon filled the church, necessitating its rebuilding, instituted mid-week Bible lectures at the infant schools and became superintendent of the district visitors’ society. His five-month success was seen in an offer of £300 increase to his stipend in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent his moving to Helmingham.

For 38 years Ryle was a parish vicar, first at Helmingham and later at Stradbroke, in Suffolk (1861-1880). Ryle became the Rector of St Mary’s Helmingham, Suffolk (1844-1861), which was some ten miles north-east of Ipswich. The squire, John Tollermarche had virtually all the parishioners in his employment at Helmingham hall or on the estate. Here Ryle found time for serious reading and study. “With an adequate stipend he was no longer dependent on gifts from his father and friends and at last could afford to buy books, even if most of them were from second-hand bookshops.”[5] He married on 29 October 1845 Matilda Charlotte Louisa, daughter of John Pemberton Plumptre MP of Fredville, Kent. They had a daughter, Georgina, but Matilda died in June 1847, having caught flu after recovering from her child-bearing.

On 21 February 1850 Ryle married Jessie Elizabeth, daughter of John Walker of Crawfordton, Dumfriesshire. She was sickly for all but her first six months of marriage, yet she gave birth to three sons; Reginald John, Herbert Edward and Arthur Johnston and a daughter Jessie Isabella. Ryle had the heavy duty of caring for his sickly wife and had “the whole business of entertaining and amusing the three boys in an evening devolved entirely upon me. In fact the whole state of things was a heavy strain upon me, both in body and mind and I often wonder how I lived through it.”[6] She eventually died of Bright’s disease in May 1860; she was only thirty eight.

Helmingham was becoming rather a trial to Ryle due to the breakdown of his relationship with the squire John Tollemarche. Both men were strong evangelicals and ought to have got on well, but perhaps they were too much alike.[7] A letter arrived from the bishop offering him Stradbroke and so moved his grieving family away from Helmingham.

Stradbroke was a small Suffolk market town with a population of some fourteen hundred people. All Saints was the parish church and had a fine fifteenth century tower which was visible for miles around. On 24 October 1861, Ryle married for the third time, Henrietta Amelia Clowes, the daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel William Legh Clowes of Broughton Old Hall, Lancashire. She had a strong faith and was able to assist him by her work in the Sunday school, playing the organ and bringing up his children.[8] She died before him in April 1889.

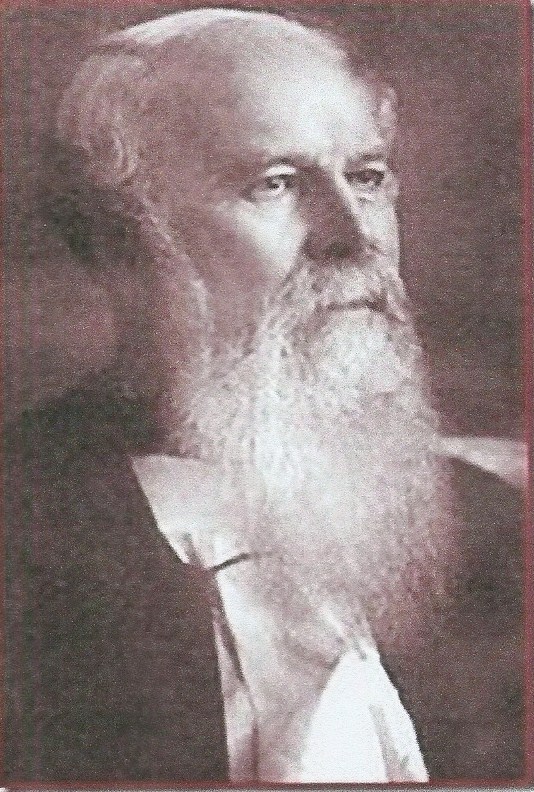

He became a recognised leader of the evangelical party in the Church of England and was noted for his forthright preaching, doctrinal essays, and polemical writings. He stood six feet three and a half inches tall, with a commanding presence, lucid oratory and became an effective popular preacher.

In 1870, Ryle became the rural dean of Hoxne and in 1872 he was made honorary canon of Norwich. Ryle was select preacher at Cambridge in 1873-4 and at Oxford in 1874-6 and 1879-80.

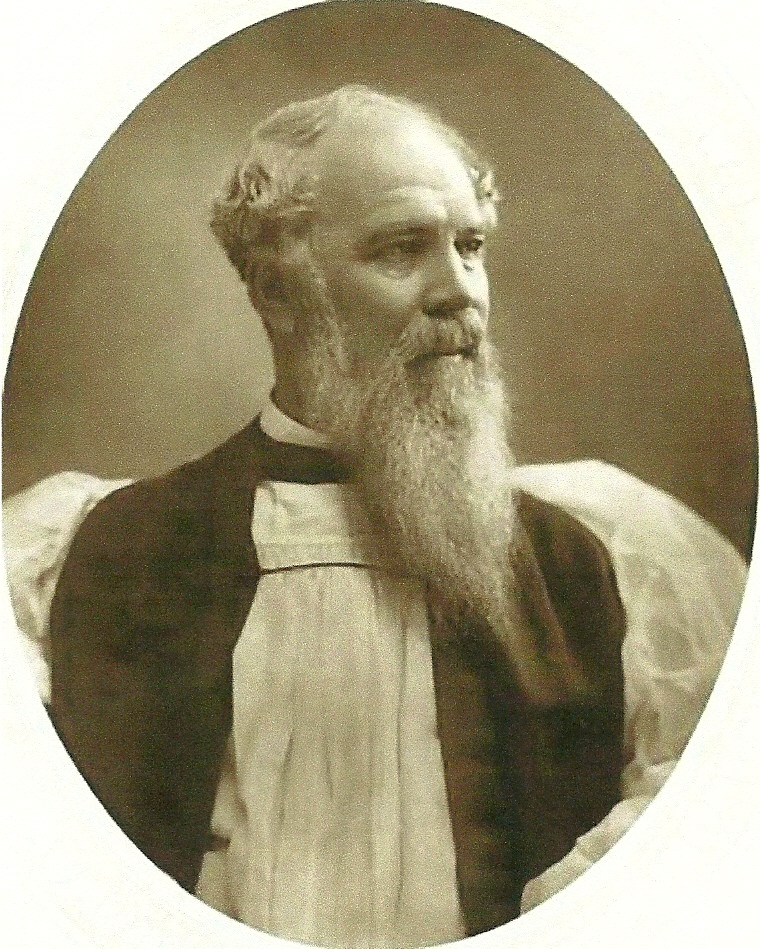

In March 1880 he accepted the offer of the deanery of Salisbury; he felt that this move would have helped him further the evangelical cause. However before taking the latter office, he was advanced to the new diocese of Liverpool, where he remained until his resignation, which took place three months before his death at Lowestoft. His appointment as Bishop to Liverpool was at the recommendation of the outgoing Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, (Lord Beaconsfield) who had just been beaten in the general election by Gladstone and wanted to place an Evangelical in a diocese to have some revenge on the High Church Gladstone; the Queen seems to have approved of the move.

In 1880, Ryle was aged 64 and as the first bishop of Liverpool would be expected to do a great deal in setting up his diocese. Liverpool was a Multinational population of 1,100,000, with some appalling poverty and living conditions. “He aimed to direct the ‘restless activity’ of the diocese by providing more ‘living agents’, an infrastructure in which they could operate, and the necessary oversight. Ryle promoted the office of Scripture Reader, paying lay men to complement the ordained ministry: ‘the lay agent may do excellent service by sowing the seed and cutting down the corn. But if the crop is not to rot on the ground, the sheaves must be bound up and stored away in the barn and this is the presbyter’s work.’ Fifty Readers took services in mission rooms, organised Sunday schools and visited the sick.”[9] In his diocese, he formed a clergy pension fund for his diocese and built forty two churches and established fifty new mission halls. Controversially, he emphasized raising clergy salaries ahead of building a cathedral for his new diocese. Ryle was described as having a commanding presence and vigorous in advocating his principles albeit with a warm disposition. He was also credited with having success in evangelizing the blue collar community.

J.C. Ryle retired on 1 March and died on 10 June, Trinity Sunday, 1900 at Helmingham House, Lowestoft aged 83. At his funeral, “The graveyard was crowded with poor people who had come in carts and vans and buses to pay the last honours to the old man—who had certainly won their love.” Canon Hobson, speaking in Ryle’s memorial sermon, said, “Few men in the nineteenth century did so much for God, for truth and for righteousness among the English-speaking race, and in the world, as our late Bishop.” Bishop Chavasse, His successor, said he was a man “who lived so as to be missed.”

He was buried in the All Saints’ Church, Childwall, Liverpool, with a Bible in his hands on 14 June. “The graveyard was crowded with poor people who had come in carts and vans and buses to pay the last honours to the old man – who certainly had won their hearts.”[10]

Ryle was a strong supporter of the evangelical school and a critic of Ritualism. He was a writer, pastor and an evangelical preacher. His second son, Herbert Edward Ryle also became a bishop, but his churchmanship was different to that of his father.

“Ryle was a man of magnificent presence. The photographs we have of him enable us to see that, but every man is much greater than his photograph. He was a man 6ft. 31/2 inches in height and straight as an arrow. There is no doubt that his beard added to his striking and commanding appearance.”[11]

Published works

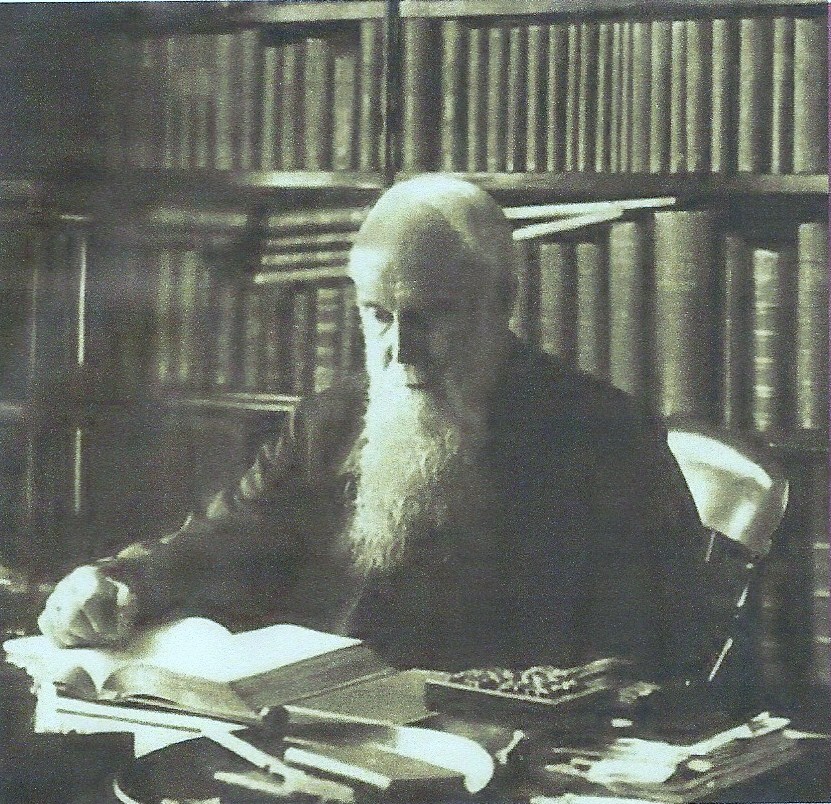

Commenting on his very deliberate writing technique, he said, “In style and composition, I frankly avow that I have studied as far as possible to be plain and pointed and to choose what an old divine calls ‘picked and packed words.’ I have tried to place myself in the position of one who is reading aloud to others.” He credits William Cobbett, the political radical; Thomas Guthrie, the Scot; John Bright, the Quaker orator; John Bunyan, Puritan and author of Pilgrim’s Progress; Matthew Henry, the great biblical commentator; and William Shakespeare, of course, as influences on his pen.

The Bishop, the Pastor and the Preacher (1854) [Studies on H. Latimer, R. Baxter, and G. Whitefield

Expository Thoughts on Matthew (1856)

Expository Thoughts on Mark (1857)

Expository Thoughts on Luke (1858)

Expository Thoughts on John (1869)

Christian Leaders of the Eighteenth Century (1869)

Christian Leaders of the Last Century (1873)

Knots Untied (1877) – has had a continuing influence as a presentation of the Evangelical Anglican position

What do we owe to the reformation? (1877)

Practical Religion: Being Plain Papers on the Daily Duties, Experience, Dangers, and Privileges of Professing Christians (1878) [Contains and “treats of the duties, dangers, experience and privileges of all who profess and call themselves Christians.”]

Holiness: Its Nature, Hindrances, Difficulties, and Roots (1877 & 1880)

Principles for Churchmen (1884)

Old Paths: being plain statements on some of the weightier matters of Christianity (N/D) [Collection of separate papers/tracts on matters of doctrine from the Evangelical viewpoint]

Light from Old Times: or Protestant Facts and Men (1890)

The Upper Room being A Few Truths for the Times (1898) [A collection of papers and addresses during his years of ministry]

Charges and Addresses (1903)

J.C. Ryle was a theological vertebrate. He never suffered from what he called a “boneless, nerveless, jellyfish condition of soul.” His convictions were not negotiable. Indeed, his successor described him as “that man of granite.” Archbishop Magee called him “the frank and manly Mr. Ryle.” Charles Spurgeon said he was “an evangelical champion . . . one of the bravest and best of men.” Ryle simply observed, “What is won dearly is priced highly and clung to firmly.” And his fortitude was not limited to doctrinal matters. As a best-selling author he used his royalties to pay his father’s debts. True character is not for sale, neither does it owe any man.

From his conversion to his burial, J.C. Ryle was entirely one-dimensional. He was a one-book man; he was steeped in Scripture; he bled Bible. As only Ryle could say, “It is still the first book which fits the child’s mind when he begins to learn religion, and the last to which the old man clings as he leaves the world.” This is why his works have lasted—and will last—they bear the stamp of eternity. They contrast fruit which “remains” (John 15:16) against wood, hay, and stubble. Today, more than a hundred years after his passing, these works stand at the crossroads between the historic faith and modern evangelicalism. Like signposts, they direct us to the “old paths.” And, like signposts, they are meant to be read.

Biographical Studies

Fitzgerald, Maurice H.: A Memoir of Herbert Edward Ryle (1928)

M. Guthrie Clark – No. 4 in the Great Churchmen Series (Church Book Room Press Ltd., 1947)

Hart, G.W.: Bishop Ryle, Man of Granite (1963)

Toon, Peter: J.C. Ryle, A Self-Portrait (1975)

Toon, P. & Smout, M.: John Charles Ryle, Evangelical Bishop (1976)

Eric Russell: That Man of Granite with the Heart of a Child (Christian Focus, 2001)

Cadle, P.J.: “John Charles Ryle”, Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals, edited Larsen, Timothy (Leicester, Inter-varsity Press, 2003)

[1] “By grace are you saved, through faith and that not of yourselves it is the gift of God” (Ephesians 2)

[2] Ryle, J.C.: A Self Portrait, p59

[3] Cadle, P.J.: “John Charles Ryle”, Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals, edited Larsen, Timothy (Leicester, Inter-varsity Press, 2003) 573

[4] Cited, Cadle, P.J.: Ibid.

[5] Russell, Eric: The Man of Granite with the Heart of a Child (Ross-shire, Christian Focus, 2001) 45:”He was particularly interested in the tomes of the Reformation and Puritan writers. These treasured volumes he picked up in Ipswich and London and occasionally from the libraries of retired clergy in the diocese ... his study of the Reformers established him in the great principles of Protestant doctrine from which he never departed.”

[6] Ibid 66: citing P. Toon: J.C. Ryle, A Self-Portrait (1975)

[7] Ibid. 68: “Ryle offered no explanation of the cause of this breakdown in relations and it was probably due to a clash of temperaments. It is sad that two strong Christians could find no way of reconciliation.”

[8] Ibid. 69: “Henrietta seems to have been a very sensible and practical woman and to Ryle’s relief, a wife who enjoyed good health. She was an accomplished musician and an expert in the new vogue of photography.”

[9] Cadle, P.J.: ibid. 574

[10] Fitzgerald, M.H.: A Memoir of Herbert Edward Ryle (1928) 135

[11] Clark, M. Guthrie: ‘J.C. Ryle’ (Great Churchmen Series, Church Book Room Press Ltd., 1947) 34